Ray Barfield and Marina Tsaplina have taken on an ambitious and important goal — to shift the focus of medicine by transforming medical education. Barfield, a professor of pediatrics and Christian philosophy at Duke University, and Tsaplina, an artist, patient activist, and scholar, formed a partnership based on their shared interest in health/medical humanities.

Together, they developed an intensive summer program for pre-med undergraduates called Reimagine Medicine, to expand the experiences, imagination, and empathy of future doctors. Unlike other pre-med programs, ReMed teaches participants to express themselves and connect with others through artistic media, such as storytelling, puppetry, creative writing, drawing, and improvisation.

We talked with Barfield and Tsaplina about the paradigm shift we need in medicine, how medical education is integral to changing the health care system, and why the skills taught in ReMed are crucial for future doctors.

Lown Institute: What is the study of “medical humanities” and why is it so important for medical education?

Marina Tsaplina: Medical humanities is a broad-ranging field of inquiry that looks at what underpins the practice and history of medicine and seeks to form a deeper understanding of health, healing, illness and disability. Medical humanities asks the questions, “What do we mean by this thing we call health or illness?” “What does it mean to attend to a body that needs care?” It also asks, “What are the systems of power in play in medicine, the patient-provider encounter, and the forces of history as related to healthcare, lived bodies, and justice?”

Ray Barfield: Nowhere in traditional medicine are we taught to ask, “What’s it like to be you? What does this health issue mean for you in your life?” When I do ask these questions, I have to imaginatively open myself to a world that’s not my own. I hear things I don’t expect and I have to respond, make it the new direction of my script. These skills of imagination, storytelling, performance, improvisation, they were no part of my training as a physician. All of these questions live in the humanities.

I think medical humanities should be the main part of medical school, with everything else in service to that. Medical schools have it completely backwards.

Tsaplina: Medicine (the medical model) says, your body is broken and needs to be fixed. But what if it is the structures around my body that need to be fixed? Or equally important, just because you are ill doesn’t mean you are not whole – and arriving at this deep inner realization is not a biological conversation.

Why is medicine taught the way it is, with biology first and humanity second?

Barfield: Part of the reason people are compelled to look at medicine biologically is that we’re afraid to die. If you say, “We can stop you from dying,” people will follow you. It’s a very powerful motivator. In medicine, death is seen as an obstacle to be overcome and physicians are seen as conquerors of death.

There’s this illusion about what medicine gives to us. At one level, sure we can control our health with medicine in some ways. But our treatments are in service to the reason we want to be alive — if we don’t know why we want to be alive, why are we doing medical interventions? Medicine has no concept of valuing what matters to you in life. Medicine’s only answer is don’t die.

Tsaplina: There has been a great spiritual error that with advanced technology, we believe that we can control life – when really our tools, our medicine, our technology – all are in service to life. A life that is ultimately, uncontrollable.

How has this mindset impacted our health care system?

Barfield: We’ve been able to use new medicines and technology to make many people’s lives better and prevent disease. We now cure over 70% of the kids that come to us with cancer [at the Duke University Medical Center]. But health care as a whole has become corporatized and massive. We’ve bought into the idea that we can control and fix every medical problem with enough technology. We have reduced people to their biology, and let them become consumer items. We’ve turned states of being like aging, into medical problems to be solved.

Tsaplina: The medical-industrial complex keeps growing larger and larger, we develop more technology, all to make us healthier. Yet as a society, we haven’t critically engaged with the ethical tensions and historic violations of human dignity that have fit themselves under definitions of “normal” and “healthy.” There isn’t an end to what medicine believes we can diagnose and fix. Even feelings, like sadness, have been medicalized.

How does the Reimagine Medicine program help shift the focus of medical education for participants?

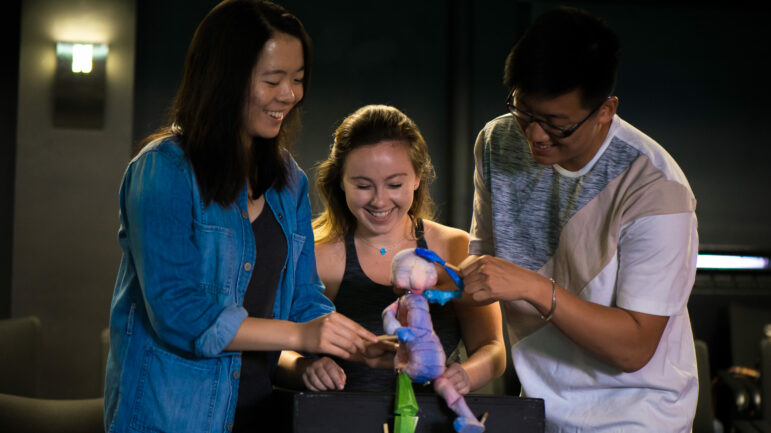

Tsaplina: Medicine doesn’t discuss how we live in our bodies. That’s what ReMed is for. In our puppetry and embodiment unit, students cultivate presence, attention, and imagination. They think about what it means to be a body in the world. They start to understand the stories of their own bodies and bodies of others.

Barfield: In the ReMed program, students get an entirely different perspective from what they’re used to. We ask artists and writers come in as themselves and bring their perspective and offer practices, not adapt themselves to the medical perspective.

How have the students felt going from ReMed back into an entirely different educational system?

Tsaplina: One of the biggest thing students walked away with was a sense of community with each other, and a hunger for community in medicine. They will move through medical school differently. It was a strategic choice to engage with students before medical school, so that those students can help reshape medical school culture from within.

Barfield: Students from last summer haven’t gotten to medical school, but they said they would stay in touch. They are a remarkable group of people. They are willing to go out of their comfort zone and stay there. We start with a limited ability to experience, but a space like ReMed can be transformative. It breaks down the sense of “us and them” between doctors and patients.

How will this program help doctors avoid moral distress and burnout, when they are up against so many obstacles in residency, like long hours, lack of sleep, etc?

Barfield: Sleeplessness is not what causes moral distress; it’s something else. It’s the disconnect between what we’re being told we’re supposed to be doing and what we feel.We conceive of every limit as an enemy, rather than something that makes life beautiful and worth living.We’re told as doctors our options are either to be a Hero or a Failure. But we’re all just people, working with others who are just people.

We’re burnt out because we’ve been practicing “disembodied medicine” — we experience patients as discrete boxes and pixelated images, not as people. With puppetry, Marina makes students aware of their own bodies and know they will eventually walk into a hospital aware of the bodies of others, resisting the abstraction. The program also fosters concrete practices that will help students flourish or at least survive medical school, like breathing, mindfulness, and awareness.

What’s next for the Reimagine Medicine program?

Barfield: We’re doing a second pilot summer program, so we’ve spent a lot of time discussing how to improve the program. We want to be better at helping students change their frame, find their true north. We’re also working with the Kenan Institute for Ethics on freshman seminars, talking about purpose and values, not just for students interested in medicine, but also in law, business, etc. We are hoping to start a ReMed program at the Duke Medical School and residency. We are also planning to hold a Reimagine Medicine conference in 2020, to bring together institutions interested in adapting the curriculum for their school, and share what we’ve learned so far.

This all started with with an artist with a long experience of illness and a doctor with a long fascination with storytelling. We have a long way to go still, but we’re figuring it out.

Marina Tsaplina is an interdisciplinary performing artist, patient activist, and scholar in the medical/health humanities and socially engaged art. As Lead Artist of Reimagine Medicine at Duke University, she is developing an embodied pedagogy for health education on the literal and poetic body in health and healing. She is founder of THE BETES Organization and is a Kienle Scholar in the Medical Humanities at the Penn State College of Medicine – Kienle Center for Humanistic Medicine. For more on narrative and social movements, see Marina’s talk at the 2015 Master Lab, hosted by Diabetes Hands Foundation/Beyond Type 1.

Ray Barfield is a pediatric oncologist, Professor of Pediatrics and Christian Philosophy, Professor in the School of Nursing, and Associate of the Duke Initiative for Science & Society at Duke University. He is a writer whose most recent books include Life in the Blind Spot and The Book of Colors. For more on the intersections between medicine and philosophy, and navigating end-of-life conversations, see Ray’s 2012 TEDx Talk and interview in The Sun.