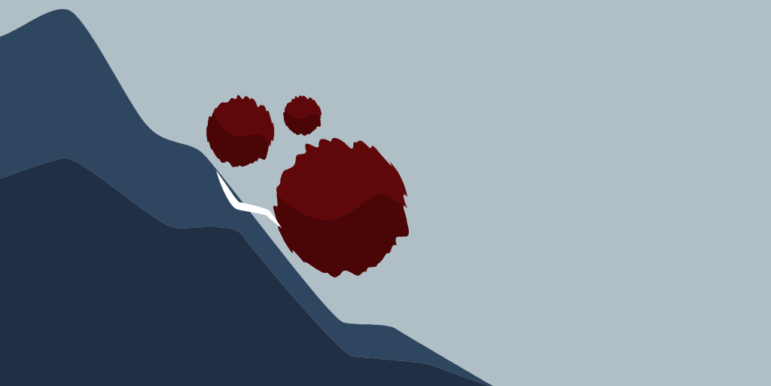

As we’ve previously written on this blog, one unnecessary procedure often leads to many more follow-up tests and procedures, increasing patient stress and the risk of harm from complications. This is known as the health care “cascade.” A few months ago, a study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 16 percent of Medicare patients who received a heart test before cataract surgery experienced a cascade event within 90 days, costing Medicare more than $35 million a year.

Overuse harm is a relatively new area of research, and there is a lot that we don’t know about care cascades. How often do they happen, what harms do they cause, and how often do they lead to harm? A new study led by Dr. Ishani Ganguli at the Harvard Medical School and colleagues (some of the same researchers who led the previous study in JAMA IM) surveyed physicians in the U.S. to better understand the frequency and harm of care cascades.

In their survey of hundreds of practicing internal medicine doctors, they found that care cascades are incredibly common, they often lead to both patient and physician harm, and that they are clinically unhelpful as frequently, if not more, than they are helpful.

Nearly 100 percent of respondents had experienced care cascades within the past year. The vast majority of physicians experienced cascades in the past year that were clinically useful and experienced those that were not useful. Thirty percent of physicians reported that they experienced cascades without a meaningful outcome on a monthly basis, compared to about 15 percent of respondents who found useful cascade outcomes on a monthly basis.

More than half of respondents said that care cascades led to patient and physician harms at least several times a year, including physical, psychological, and financial harm to patients and wasted time and frustration for physicians.

Why are care cascades so common? The survey offers some answers to this question as well. Among survey respondents, the most commonly reported reasons for pursuing additional tests after an incidental finding were that they thought the finding could be clinically important, they were following the norms of their institutional culture, they were concerned about being sued, or because the patient asked for follow up.

They survey also points to ways in which harm from care cascades might be avoided. In the absence of guidelines to help physicians decide when to pursue additional tests after an incidental finding, most rely on their fellow physicians, patients’ desires, and their practice norms. We need to do more to educate clinicians and patients, and to change institutional and societal norms to allow for more acceptance of uncertainty and understanding of the risks of overuse.

As Dr. John Mandrola, cardiologist at Baptist Health, and Dr. Dan Morgan at the University of Maryland School of Medicine point out in an accompanying commentary, there is little public awareness about the harms of overdiagnosis. While every disease has a month for awareness, there is no “Overdiagnosis Awareness Month.” Therefore, patients may expect follow up for incidental findings and not anticipate the downsides of these tests and procedures.

As Ganguli et al. point out, the fact that physicians do find clinically meaningful outcomes from cascades sometimes may encourage physicians to keep testing incidental findings, or make them afraid not to do a workup. Because these decisions are tough, institutional support and appropriate malpractice reform can help support physicians in delivering right care.

Of course, the easiest way to prevent harm from cascades is to avoid unnecessary imaging in the first place. According to the JAMA study, about one-third of respondents said that the initial test that started their most recent cascade may not have been medically necessary. Mandrola and Morgan write that doctors can help prevent future cascades by thinking ahead. “Looking upstream in a cascade to the initial inappropriate test done in the name of safety is a type of medical error that needs further exploration,” they write.