The most inclusive hospitals get the least amount of radiology research funding, study finds

The Lown Institute’s research on hospital inclusivity shows that hospital markets are often segregated, with some hospitals serving disproportionately more low-income patients and patients of color than other hospitals. Is there a relationship between hospital inclusivity and the funding they receive from government grants? A new study explains…

Equity rankings and funding

In a recent study in the journal Radiology, researchers from Drexel University College of Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Denver Health, and other institutions examined whether hospital inclusivity and community benefit grades on the Lown Index were associated with amount of radiology research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 2017-2021.

Among the 75 hospitals in the study, they found a negative relationship between NIH funding and inclusivity — that is, hospitals that were more inclusive of lower-income patients, patients with lower levels of education, and patients of color, received less funding.

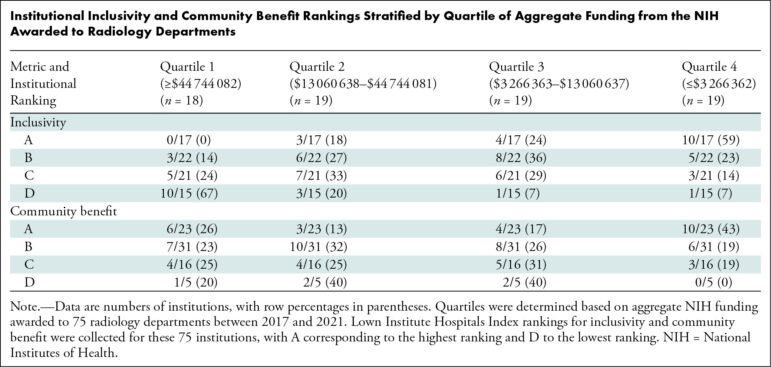

The differences were striking. Among hospitals receiving an A grade for inclusivity, none were in the top quartile of funding (over $44 million) and 59% were in the bottom quartile (less than $3.2 million). Of those with D grades in inclusivity, 67% were in the top quartile and 7% in the bottom.

There was not a statistically significant relationship between Lown Index Community Benefit rank and funding. Hospitals were about as likely to be in the top quartile of funding regardless of their community benefit grade, although hospitals with “A” grades in Community Benefit were more likely to be in the lower quartile compared to hospitals with lower grades.

What explains these differences?

There are several possible reasons why more inclusive hospitals tend to get less NIH funding for their radiology departments. In an accompanying editorial in Radiology, Dr. Tejas Mehta and Dr. Max Rosen from the Department of Radiology at UMass Memorial Medical Center explain that the types of hospitals that tend to get the most funding from the NIH (generally large academic medical centers) are often inaccessible to lower-income patients.

“At these well-resourced institutions, a patient’s lack of health insurance, limited access to transportation, and limited health literacy are barriers to care in under-resourced communities.”

Dr. Tejas Mehta and Dr. Max Rosen, Radiology

Despite their crucial role providing care in underserved areas, it’s often the most inclusive hospitals that are struggling financially. For example, Wellstar Health System in Georgia closed their Atlanta hospital, which was among the most inclusive in the state, citing financial challenges. Several other safety net hospitals have closed or reduced services in recent years as well. Lower levels of resources make it more difficult for inclusive hospitals to apply for and receive lots of grants.

This study also shows that radiology funding is highly uneven among hospitals– the top 20% of radiology departments by funding earned approximately 66% of the funds provided by the NIH between 2017 and 2021. This makes the disparity between the “haves” and “have-nots” very clear when it comes to funding.

Improving inclusivity

If hospitals receiving the most funding are inaccessible to under-resourced communities, that can have an impact on access to clinical trials and new treatments. Improving clinical trial diversity is a stated objective for research institutions and government regulators; if institutions with the most funding and biggest projects aren’t accessible, that’s a threat to trial diversity.

Drs. Mehta and Rosen suggest that strengthening relationships between well-funded academic medical centers and more inclusive community hospitals can help ensure that everyone has access to clinical trials.

That’s a worthy goal, but it only solves part of the problem. More-inclusive hospitals will still be at a financial disadvantage because of our two-tiered system. Hospitals get paid the most to perform high-tech elective surgeries for patients with private insurance but barely break even on preventive or routine care for patients with Medicare or Medicaid. This means their financial success often depends on attracting wealthier patients with private insurance, patients who are more likely to be white. We need real healthcare transformation to combat these inequalities in funding and access.