Thirty percent of Covid-19 patients were prescribed antibiotics in outpatient setting

A recent study in JAMA finds that during the first year of the pandemic, many providers in the emergency department (ED) and other outpatient settings gave antibiotics to older adults with Covid-19, despite there being no evidence for their benefit in treating viruses.

An overprescribing epidemic

Over the past two years, we’ve developed vaccines, treatments, and other standards of care for Covid-19 that reduce the risk of severe illness and death. But during the first waves of the pandemic, there was little evidence on the best treatments for the virus, leading many doctors to experiment with unproven therapies like malaria drugs, anti-parasitics, and blood thinners.

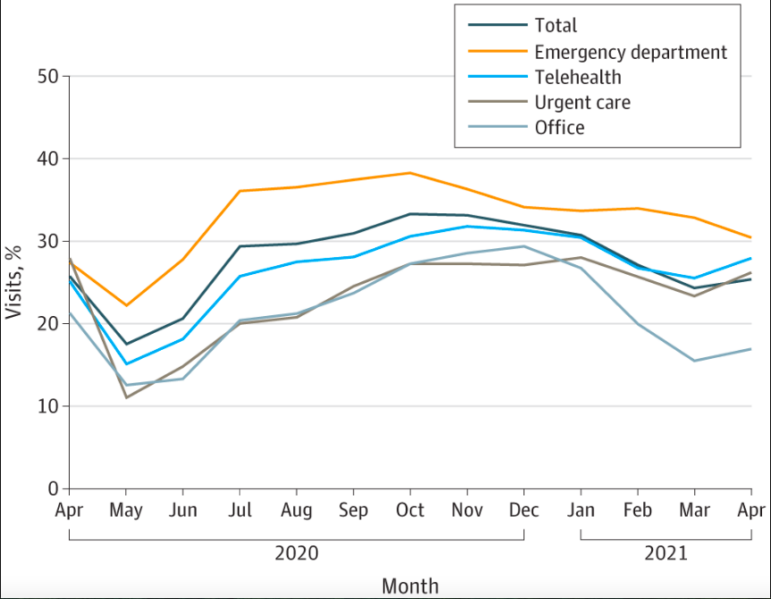

Antibiotics, which were commonly overused before Covid-19, became another treatment that was widely prescribed to Covid-19 patients with no evidence of benefit. In a recent research letter in JAMA, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that about 30% of Medicare beneficiaries with Covid-19 as the primary diagnosis received an antibiotic in outpatient settings such as the ED, urgent care, telehealth, and doctor’s offices, from April 2020-2021.

Rates of antibiotic prescribing were highest in the ED, with more than one third of Covid-19 patients receiving a prescription, followed by telehealth and urgent care. Rates of prescribing were highest in October 2020, leading up to the winter Covid-19 surge.

Comparing regional prescribing rates, antibiotics were most likely to be prescribed in outpatient settings in the South (37%) and least likely in the Northeast (22%). This pattern tracks with previous research showing greater rates of overuse in the South compared to other regions.

Drivers of antibiotics for Covid-19

Why did so many clinicians prescribe antibiotics for Covid-19 with no evidence to support it, especially given the harm of antibiotic resistance?

Many doctors likely prescribed antibiotics to Covid-19 patients because they feared the possibility of “secondary infections,” when damage caused to the nose or lungs from a virus leads to a bacterial infection. Early reports from China had warned about drug-resistant infections in Covid-19 patients, but doctors later found that these warnings turned out to be overly cautious.

For some doctors, using antibiotics was an act of desperation early in the pandemic, driven by a lack of effective treatments.”Many physicians were inappropriately giving antibiotics because, honestly, they had limited choices,” said Dr. Teena Chopra, director of epidemiology and antibiotic stewardship at Detroit Medical Center, in The New York Times.

Many clinicians do not see antibiotic resistance as a real threat, despite the fact that 2.8 million of these infections occur every year. Especially in the stress of a pandemic, the constant drive for clinicians to “do something” can be more powerful than the future potential threat of superbugs.

The ease of prescribing antibiotics through telehealth visits may also be a factor. Direct-to-consumer telehealth visits had high rates of antibiotic prescribing for children with upper respiratory viruses before Covid-19. The inability to do a close examination via telehealth as well as the need to keep patient satisfaction rates high may result in a “better safe than sorry” approach.

Unnecessary antibiotics and race

In the CDC study, the authors found that antibiotics were more often prescribed to non-Hispanic white Medicare patients with Covid-19 (31%) compared to Black (23%), Hispanic (29%), Asian American/Pacific Islander (27%), or American Indian/Alaska Native (24%) patients with Covid-19.

This result is counterintuitive because prior to Covid-19, Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to receive inappropriate antibiotics. A recent study from researchers at the University of Texas at Austin found between 2009 and 2016 in outpatient settings, almost 64% of antibiotic prescriptions written for Black patients and 58% for Hispanic patients were inappropriate, compared to 56% for white patients. The University of Texas researchers posited that lack of access to follow-up care in communities of color may drive overprescription of antibiotics; if providers feared patients may get an infection and that they wouldn’t be able to come back to receive medications, they would be more likely to prescribe antibiotics.

The opposite pattern found in the CDC study may reflect the inequality of resources available in white neighborhoods during Covid-19, compared to communities of color. Hospitals serving more people of color were overwhelmed during the pandemic and at times ran out of beds and supplies. Providers serving white communities may have been able to offer more in the way of Covid-19 treatments — both beneficial and non-beneficial ones. Throughout the pandemic, the most privileged Americans have received the “more is better” treatment, while the most marginalized are denied basic lifesaving care.

The overprescription of antibiotics for Covid-19 patients provides several lessons on overuse in general: 1) uncertainty and lack of evidence can be major drivers of overuse, 2) care setting and location matter (and “virtual” settings matter as well), and 3) structural racism can lead both to underuse and overuse for people of color.