“Nudging” doctors to reduce overuse

Overuse, also known as low-value care, refers to medical services that provide little or no benefit to patients. These unnecessary services take a large toll on our health system, exposing millions of patients to risk of harm and wasting hundreds of billions of dollars.

While the policy landscape undoubtedly creates incentives for overuse, overuse rates often come down to the differences in behavior among individual physicians. Like all of us, physicians are vulnerable to cognitive biases, like availability bias (when we give more importance to examples we more readily remember), confirmation bias (when we give more importance to information that confirms our existing beliefs), and loss aversion (when we fear the outcome of losing something more than anticipate the value of gaining something). These can all impact decisions to offer low-value services to patients.

Nudges to reduce overuse in primary care

How can we combat cognitive biases and reduce overuse? A recent randomized controlled trial in JAMA Internal Medicine shows how techniques from behavioral economics can “nudge” doctors into reducing low-value care.

Researchers from the University of Michigan tested three methods from behavioral economics on 81 primary care clinicians:

- Using nonbinding precommitment – Clinicians were asked to make a written commitment to follow three Choosing Wisely recommendations for older adults (avoiding intensive diabetes medications, avoiding sedative-hypnotic medications for insomnia or anxiety, and avoiding prostate cancer screening for patients over 75).

- Supporting deliberative thinking at the point of care- To counteract reflexive quick decisions that can diverge from evidence, clinicians received an EHR reminder when patients for whom the Choosing Wisely recommendations might apply came to the clinic. Clinicians were also given handouts about the recommendations they could use during the visit and were send weekly emails with strategies to help reduce low-value care.

- Providing social information about what peers decided to do – “To remind clinicians of their commitment and signal social norms to avoid use of low-value services, photographs of committed clinicians appeared on posters in public waiting areas and exam rooms,” the study authors wrote.

The intervention was implemented across eight primary care clinics, with the starting date for each clinic determined randomly. The prevalence of low-value care was measured in each clinic before the intervention started (control group) and after (intervention group).

The intervention had positive, if moderate, results. Of the 81 clinicians who participated, all made the commitment to following the recommendations. In the control group, there were 20.5% of patient-months in which a patient received low-value care, compared to 16% in the intervention group. The odds of having a low-value service in a given month was 20% lower in the intervention group.

“Use of such scalable interventions that nudge patients and clinicians to achieve greater value while preserving autonomy in decision-making should be explored broadly.”

Kullgren et al., JAMA Internal Medicine

In particular, the intervention group had an 85% greater odds of de-intensification of diabetes medications (reducing the use of powerful diabetes drugs that are not recommended for older adults). However, the same difference was not seen for sedative-hypnotic medications for insomnia or anxiety.

When viewing each recommendation individually, no patient cohort showed statistically significant reductions in low-value care (this may be due to the lower number of patients in each cohort making these differences hard to detect).

The “4 E’s” to reduce hospital overuse

The University of Michigan trial shows that implementing multi-component behavioral interventions can help reduce some types of common overuse in primary care. But what about reducing overuse at hospitals, where low-value care is prevalent?

In JAMA Internal Medicine, low-value care experts Dr. William K. Silverstein and Dr. Jerome A. Leis from the University of Toronto and Dr. Christopher Moriates from UCLA explain how hospital units can reduce common types of low-value care like putting in a urinary catheters without an indication or doing repetitive blood tests.

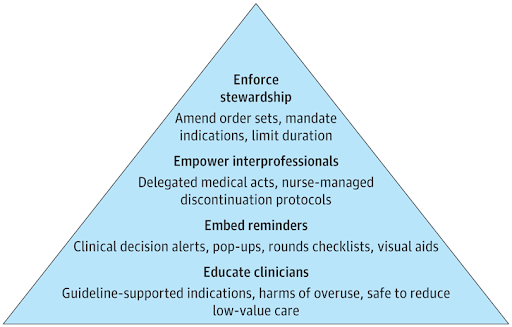

They propose a quality improvement model called the “4 E’s” for reducing overuse: Educate clinicians, Embed reminders, Empower interprofessionals, and Enforce stewardship.

The first two Es (which were also part of the University of Michigan study) are easier to implement–but these alone won’t solve the problem, Silverstein and colleagues write. Once hospitals have implemented educational interventions and EHR reminders, the next step is to get nurses involved and empower them to discontinue low-value care. For example, hospitals can implement medical directives that allow nurses to stop low-value care in certain circumstances.

Lastly, “hardwiring rules” into the EHR can automate low-value care in certain cases. One example of this is reducing repetitive blood work in the hospital by “removing the ability to order daily laboratory tests or limiting ordering to a prespecified duration” in the EHR.

Whether it’s in primary care or at the hospital, it’s encouraging to see more promising strategies for reducing low-value care.