What’s up with hospital finances?

Hospitals are in dire financial straits, hemorrhaging money from contract labor and low volumes. No wait, hospitals are financially healthy with years worth of cash on hand for rainy days. What’s really going on with hospital finances? The short answer is, it depends on the type of hospital and the metric you look at. Let’s dig in.

What happened in 2020-2021?

To understand where we are now, we have to go back a few years to the beginning of the pandemic. COVID-19 created serious financial challenges for hospitals. While hospitals struggled with acquiring personal protective equipment and trying to keep their staff and patients safe, their volume of lucrative elective procedures plummeted. In May 2020, the American Hospitals Association warned that hospitals were losing $50 billion each month.

Fortunately for hospitals, the cavalry came in the form of the CARES Act. Healthcare providers received $67 billion in general relief funds to compensate for reduced Medicare reimbursements, and $30 billion in targeted funds was later provided to rural providers and those in areas especially impacted by COVID-19.

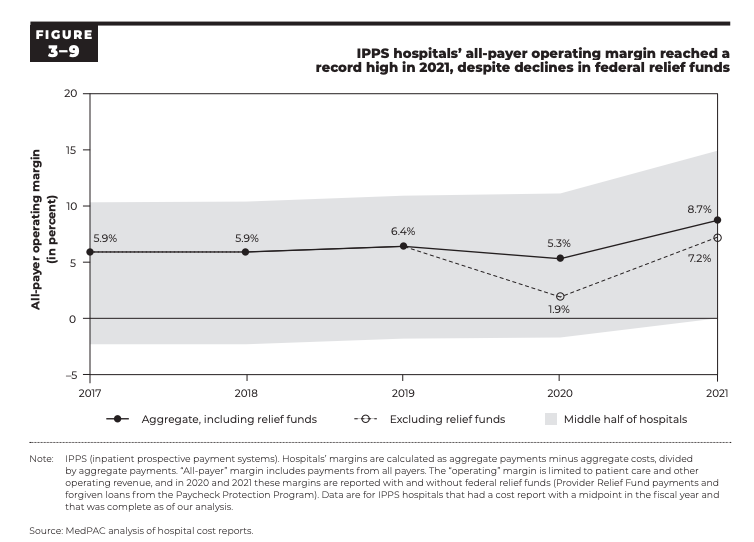

Did the payments work to protect hospitals? In general, yes. According to a recent report from MedPAC, an independent legislative branch agency that analyses Medicare data, average hospital operating margins stayed above 5% in 2020 and 2021, mostly due to the boost from provider relief funds. In fact, hospital operating margins hit a record high in 2021 at 8.7%. This analysis tracks with other studies showing that provider relief funds provided a buffer for hospitals overall.

However, not all types of hospitals were affected equally. A study last year in JAMA Health Forum on the financial outcomes of COVID-19 on California hospitals found that safety net hospitals (those with high share of publicly insured patients) were hit particularly hard in the first year of the pandemic, experiencing operating losses more than $3 billion in total.

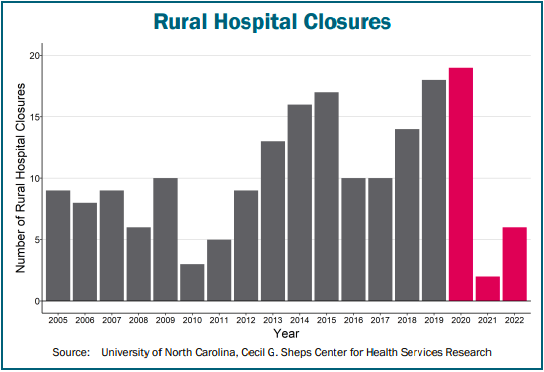

Rural hospitals were especially helped by COVID-19 relief funding; however, for many hospitals, this help came too late. Research on rural hospital closures from the Cecil G. Sheps Center at UNC shows that 19 rural hospitals either closed or converted to urgent care or outpatient only in 2020, an apex in the trend of increasing hospital closures since 2017. However, in 2021 only three rural hospitals converted and none closed outright, which may have been due to the funding boost from the CARES Act.

2022: A crisis year for hospitals?

Most hospitals made it out of the early pandemic okay, but in 2022 they were hit with the Omicron wave of COVID-19, RSV and other viruses, severe staffing issues, and the end of provider relief funding.

Overall, median hospital operating margins were negative every month of 2022 except December, according to a Kaufman Hall report using a sample of 900 hospitals across the US. This means that most hospitals were losing money on patient care services.

If COVID-19 relief funding was a band-aid on rural hospital finances, 2022 saw this band-aid ripped off, putting many rural hospitals back in dire financial straits. Rural hospitals in states that have not expanded Medicaid have been especially burdened by uncompensated care for uninsured patients. Seven rural hospitals closed or converted in 2022, and a whopping 200 rural hospitals are estimated to be at risk of immediate closure due to their persistent negative margins and low assets.

What really got the attention of the media was the poor financial performance of large nonprofit systems like Kaiser Permanente, Mass General Brigham, and the Cleveland Clinic. If even these powerhouse systems are struggling, hospitals must really be in trouble, right?

Well, not necessarily. In a recent article in Health Affairs, researchers examined financial reports at ten large nonprofit hospital systems for 2021 and 2022. They found that total system profit margins declined from 9% in 2021 to -6% in 2022, a whopping 164% decrease. But… most of this change was due to a decline in investment revenue, not the cost of providing patient services, researchers found. In fact, patient service margins overall slightly increased from 2021 to 2022. So what appears to be large systems in dire financial straits may just be a reflection of a temporary dip in stock values.

“When losses are driven by risky financial investments, it is not clear whether patients, employers, insurers, and taxpayers should be responsible for paying higher prices to offset the impact of overall market declines.”

Christopher M. Whaley, Sebahattin Demirkan, & Ge Bai, “What’s Behind Losses At Large Nonprofit Health Systems?”, Health Affairs, March 24 2023

And in fact, for many hospitals, their investment income bounced back. A STAT News analysis of 37 nonprofit hospital systems’ financial records for the last quarter of 2022 showed that all but five showed higher investment gains than the same time period in 2021. This provides a buffer for low operating revenue among hospitals lucky enough to have investment income that they can liquidate quickly.

Where are we now?

So far this year, hospitals’ median operating margins are looking better than last year, according to the latest Kaufman Hall report. However, there are differences by hospital size. For hospitals with 500 or more beds, operating margins are 50% higher this year so far compared to last year, while hospitals with 0-25 beds are seeing operating margins no better than last year.

Rural hospitals closures have not slowed either; so far in 2023, eight rural hospitals have closed or converted. That includes three hospitals that have converted to “Rural Emergency Hospitals,” a new CMS designation that requires hospitals to stop inpatient care in exchange for additional payments to keep their emergency rooms open.Low operating margins have made small rural hospitals vulnerable not only to closure but to acquisition by other systems or private equity-backed companies. According to a recent Private Equity Stakeholder report, at least 130 rural hospitals are owned by private equity firms.

Out of all this financial information, what can we learn? Certainly there are lessons to learn about the importance of looking at variation in financial positions among different types of hospitals, and between operating and non-operating margins.

But my biggest takeaway from this saga of hospital finances is that the way we pay hospitals makes no sense. We require hospitals to chase privately-insured patients and prioritize elective procedures rather than devote resources where they’re most needed in their communities. The fact that health systems have felt compelled to close or convert safety net hospitals like Wellstar Atlanta and St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland shows how our system makes it nearly impossible for hospitals to be socially responsible and stay afloat.