Is there an “equitable” way to sue patients for medical bills?

The #1 spot on this year’s Shkreli Awards (the Lown Institute’s list of the worst examples of profiteering and dysfunction in health care) went to the hospitals that sued patients for unpaid medical bills and garnished patients’ wages. Some hospitals, like Froedert & the Medical College of Wisconsin Network, continued to sue patients during the pandemic, until they were called out by Wisconsin Watch.

How can we stop hospitals from suing patients and improve the fairness of hospital billing practices in general? The Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) recently released an updated set of best practices for the “equitable” resolution of medical accounts. The guidelines, created in collaboration with hospital leaders, collection agencies, and community watchdog groups, have been hailed for encouraging a “focus on racial equity” in billing practices. But while there are some valuable recommendations, in general these guidelines do not go far enough to lift the burden of high health care costs on patients.

Extraordinary collection actions

First, the good news. The HFMA report identifies some important avenues for policy on fair billing. One of the most important recommendations is for hospitals to provide a “high-level review of the Extraordinary Collection Actions (ECAs) allowed and the circumstances in which they are allowed under the current account resolution policy.” ECAs include actions like suing patients, garnishing wages, selling debt to a third party, or credit reporting. The HFMA report recommends detailed hospital reports on ECAs, including the rate at which ECAs are used, how much money was collected from these actions, and the race/ethnicity of the patients against which the actions were taken.

When researchers and media reports cast a spotlight on hospitals that sue patients, it makes a difference. Negative attention calling out hospitals for these practices have led many hospitals to stop further lawsuits against patients. Reporting has also brought to light the fact that hospitals tend to sue those who cannot afford to pay, and they make little money from these collection actions (a report on Texas hospitals found that they made only 0.15% of their revenue from these lawsuits). In fact, in several cases the CEO of the hospital was not aware that their hospital took these actions at all. Having this information out in the open would go a long way toward reducing the number of ECAs.

The HFMA guidelines encourage hospital leaders to weigh the risk of ECAs (for both the patient and the hospital) against the potential yield (which is usually small) before going forward with these actions. The guidelines also acknowledge that in the extraordinary time of Covid-19, hospitals should consider ceasing ECAs. Yet the HFMA guidelines do not go so far as to recommend that hospitals stop ECAs entirely, although patient advocates and doctors alike have urged hospitals to stop suing patients. Instead, the guidelines include a long list of prerequisites before hospitals decide to sue patients, such as screening patients for financial assistance eligibility and various other “indicators of indigence.” The idea behind these criteria is that hospitals should only be suing people who can afford to pay the medical bills they are given.

But the question remains, should nonprofit hospitals that receive millions in tax breaks be taking these extraordinary collection actions against patients–especially considering that many of these hospitals could be providing much more in charity care than they do currently?

Price transparency

The HFMA report identifies another important question around billing– when should hospital representatives talk to patients about financial issues? Too often, patients have a procedure done and then get hit with a bill much higher than they expected. Some of the recommendations in the HFMA report are designed to combat this issue, by urging providers to provide price estimates and plain-language explanations of billing processes before the patient receives care, when possible.

However, there are a few problems with this strategy. First, often patients inquire about how much a procedure will cost and providers have no idea. This is because prices are rarely set in hospitals, but depend on negotiations between the hospital and the insurer. The HFMA report tells providers to “refer patients to their health plans” if a price estimate does not exist, which often just turns into a merry-go-round of being referred back and forth from the hospital to the insurer and never actually getting a price.

Second, a lack of coordination between clinicians and administrative staff can make these financial discussions confusing for patients. If a patient is unexpectedly contacted about financial issues right before they receive treatment, this can add to stress or avoidance necessary care. Sometimes, financial discussion morph into requests for payment upfront, which makes it seem as though patients are being “held hostage” for their care by the financial demands of the hospital.

Is there a better way?

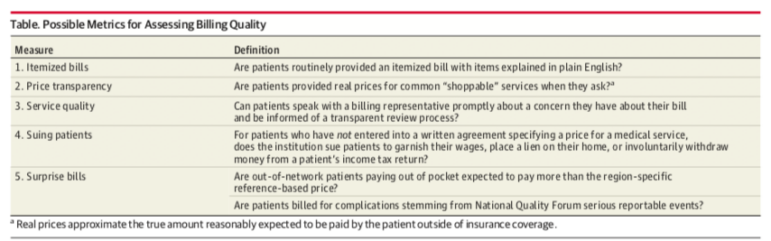

Patient advocates have been vocal about what they want from hospitals in terms of billing: Transparent shoppable prices, itemized bills with no surprises, and no extraordinary collection practices. Clinicians too are frustrated watching their patients struggle to pay for needed care. In an viewpoint article in JAMA earlier this year, Simon Matthews and Marty Makary at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine proposed a set of metrics on which hospitals could be assessed for the quality of their billing practices. Incorporating these metrics into hospital rankings and other assessments could lead to meaningful improvements in hospital billing practices.